Your Cart is Empty

Trust your Porsche's servicing to PR Technology

BY Dino Dalle Carbonare

Credit: http://www.speedhunters.com/

For the past few years we’ve seen the continuous evolution of aerodynamic packages on cars entered in the World Time Attack Challenge. It’s always been something I’ve looked forward to seeing with my own eyes at Sydney Motorsport Park on the set up day of the event, embarking on a pit walk and stopping at each garage to check out what wild solutions teams have come up with. For 2018, however, it seems like we’ve pretty much hit a wall.

Sure, the refinements to aero are there, but they are more to do with fine tuning. They’re hard-to-spot changes that don’t catch the eye. It makes sense and is something that sooner or later had to happen; no one could expect things to progress at the same rate year in and year out.

There may still be solutions around the corner that edge things on further – who knows what guys like Andrew Brilliant are working on next – but I think we’ve pretty much reached the highest point of aerodynamic experimentation in time attack.

It was obvious at WTAC this year that the more extreme cars hadn’t evolved much further. Thus, I wanted to dig a little deeper and see if there was any common thing that teams had been working on over the last year of R&D.

Of course, generating high levels of downforce also means you are introducing equally high levels of drag, and to combat this and get the car to the speeds it needs to be at in order to generate said downforce, power becomes a very important aspect. It really is a vicious circle. The RP968 team are the hands-down winner at this; their monster 4.0-liter four cylinder billet engine is a real powerhouse that’s rumored to produce 1,300hp in race trim, but able to more than double that if it was tuned for drag use (not that they will, it’s just to give an idea of how strong it is).

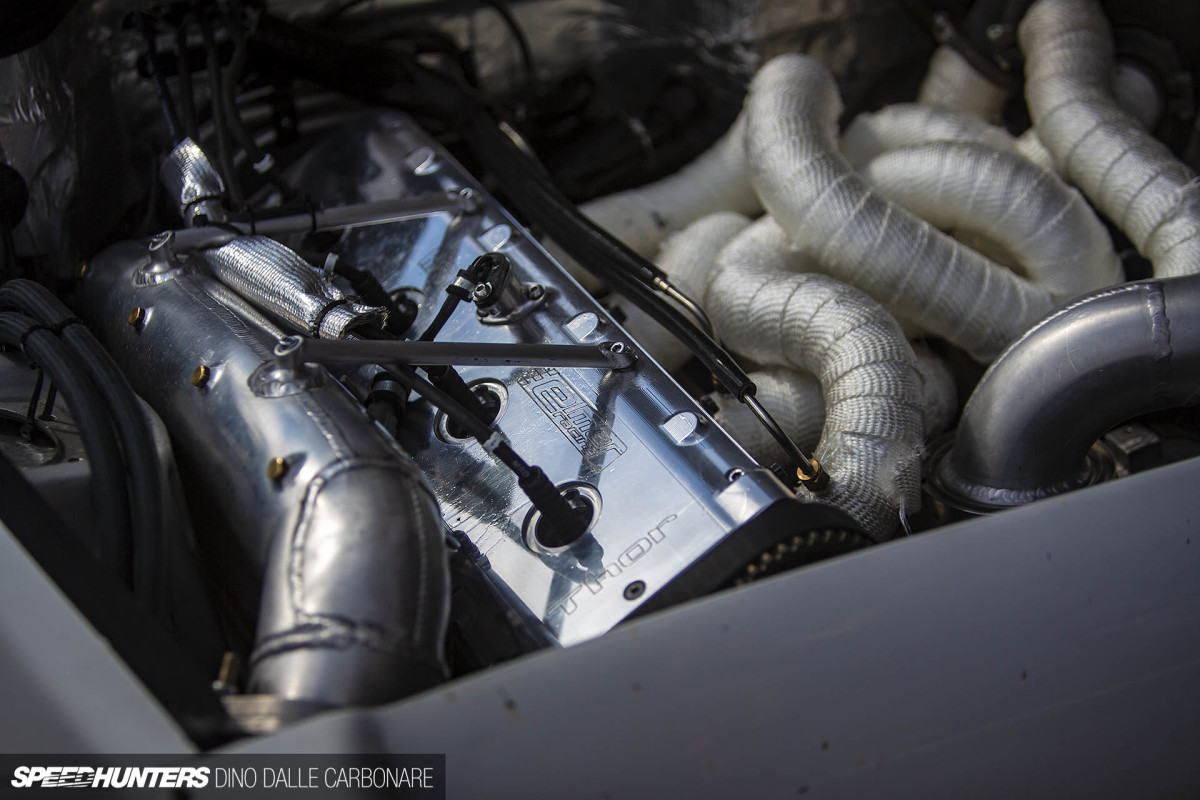

‘Thor’ is the name given to this massive inline four built by Elmer Racing Engines in Finland, and it’s a thing of beauty. From what has to be the most complex exhaust manifold in existence, to the twin wastegate setup needed to control the generously sized turbo, I couldn’t help but take a look every time I passed by the car in the PR Tech pit garage. I just love seeing how time attack cars now need drag motors to realize their maximum potential

Look around builds like this Porsche and you realize that they’re essentially unrestricted and uncategorized race cars, right down to the cockpits. Some people might look at this as something to criticize, but I personally think there isn’t enough of this happening. There should always be aspects of motorsport that allow engineers and the teams behind the cars to push things with no or little limitations, just to see what can be achieved.

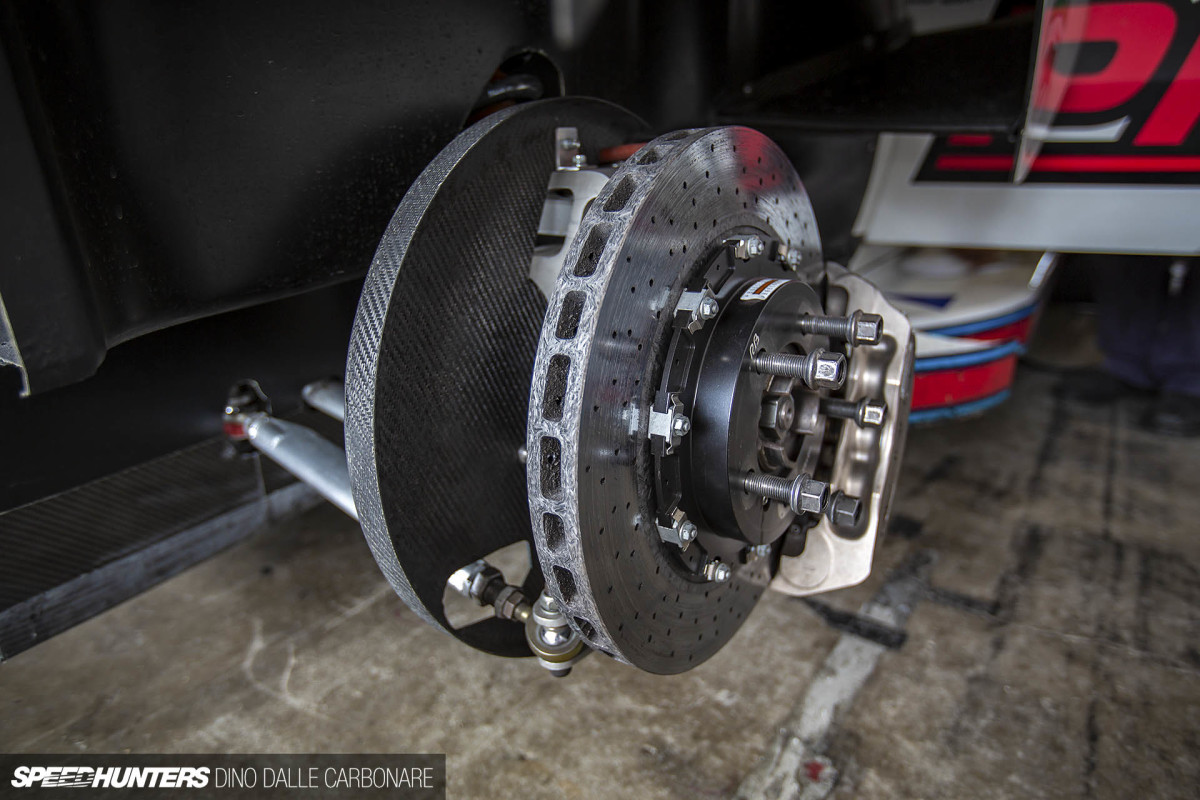

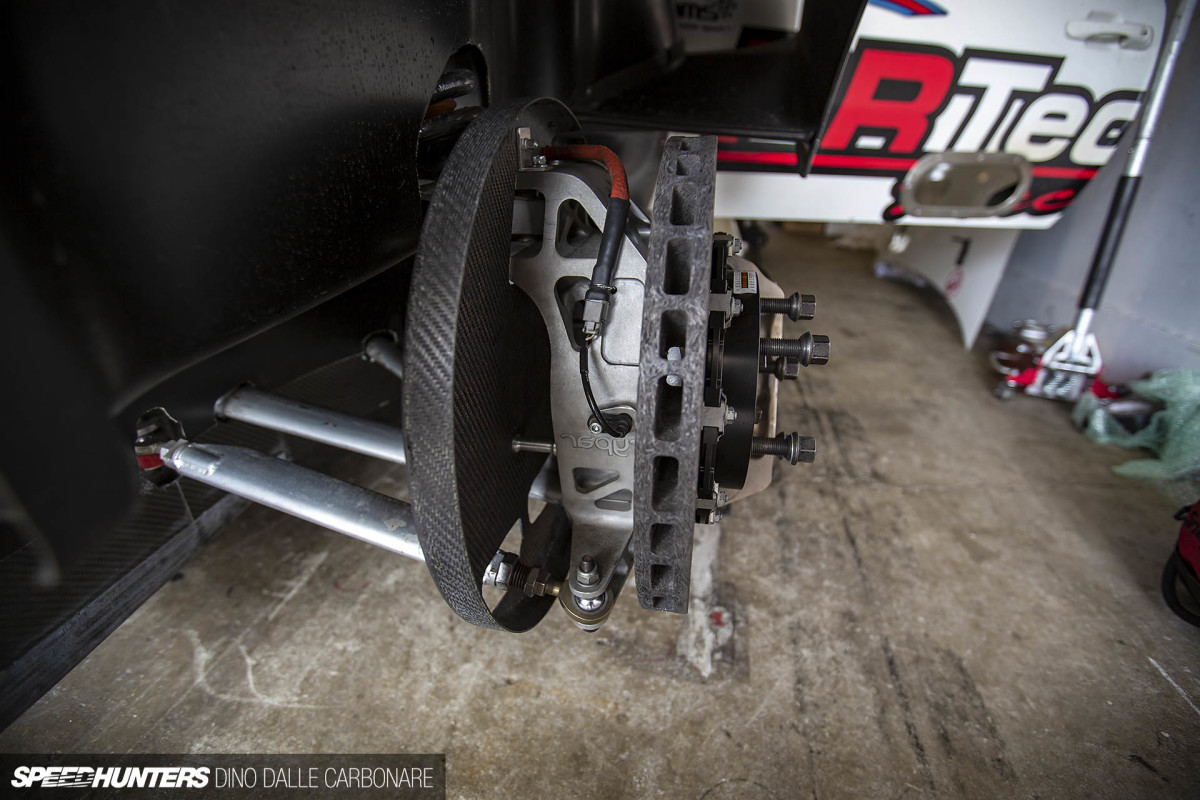

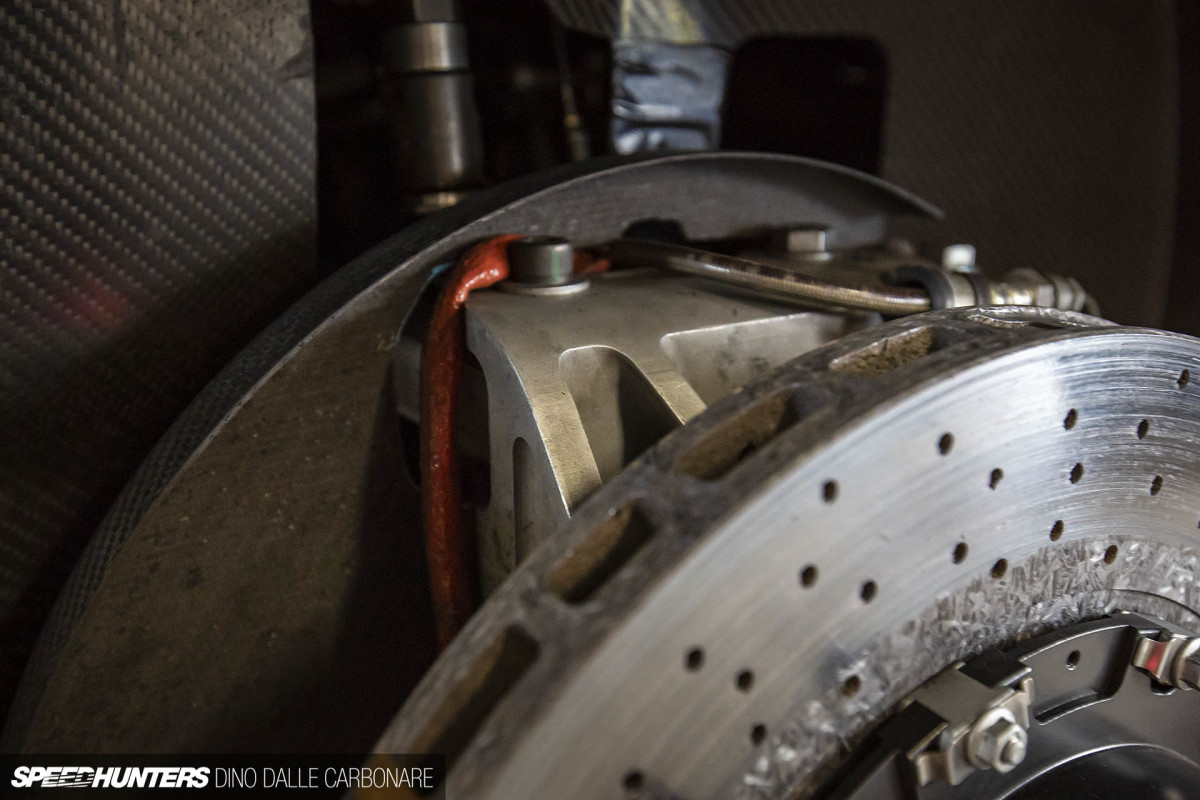

One area that many teams appeared to be working on and trying to improve this year was suspension and brakes. More and more teams have made the jump to either carbon-ceramic rotors or carbon-carbon rotors/pads, to not only get the braking performance required at this level, but also a substantial weight reduction where it counts the most: unsprung mass.

These are the carbon-ceramic front discs that the RP968 uses, mated to 6-pot Porsche race calipers positioned as low as possible to keep weight distribution in check.

It’s all mounted to another component that has become a very important part to address: the upright. Components like these Brypar units have slowly but surely been making their way into this form of motorsport. It’s something that was not even considered until tech had been pushed to the point it is now, but these days it’s become an indispensable part of any Pro car at WTAC.

A lightweight billet upright brings nothing but advantages, from the ability to customize it to match the suspension layout you want to use front or back, to geometry adjustability, lightness, ability to rethink caliper location, integrate different steering boxes, and use motorsport wheel bearings. The latter is especially interesting as these are the first components that suffer when you start loading up aero downforce.